Using aerial surveying, analysis, and field verification, also called ground-truthing, marine biologists from Atkins North America have found an increase in seagrass in the Sebastian Inlet shoal-wide, approximately 6.24 acres, and no new boat propeller scarring, in stark contrast to the Indian River Lagoon-wide trend.

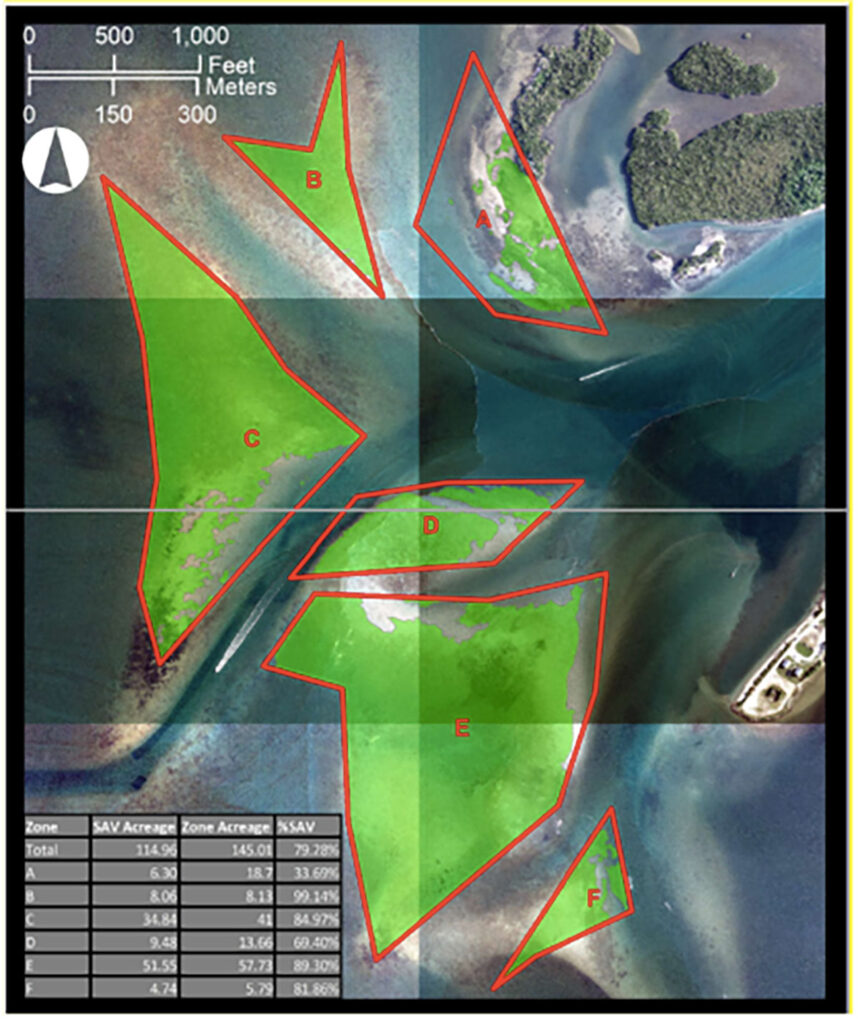

The 145-acre area, divided into six zones and monitored annually, contained six of the seven different species of seagrasses found in the Indian River Lagoon, including shoal grass (Halodule wrightii), manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), paddle grass (Halophila decipiens), threatened Johnson’s seagrass (Halophila johnsonii), star grass (Halophila engelmannii) and turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum).

Each one of the zones showed a net increase. Seagrass coverage totaled 114.96 acres in the area surveyed.

Zone-specific seagrass acreage estimates ranged from 4.74 acres in Zone F to 51.55 acres in Zone E with the percentage of the zone area covered by seagrass from 33.69% in Zone A to 99.14% in Zone B (see Figure 1).

This biological monitoring dates back to the District’s 2007 channel extension project to connect the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) to Sebastian Inlet with a 3,120-foot marked channel for boaters and was part of a comprehensive mitigation strategy to protect sensitive seagrass habitat.

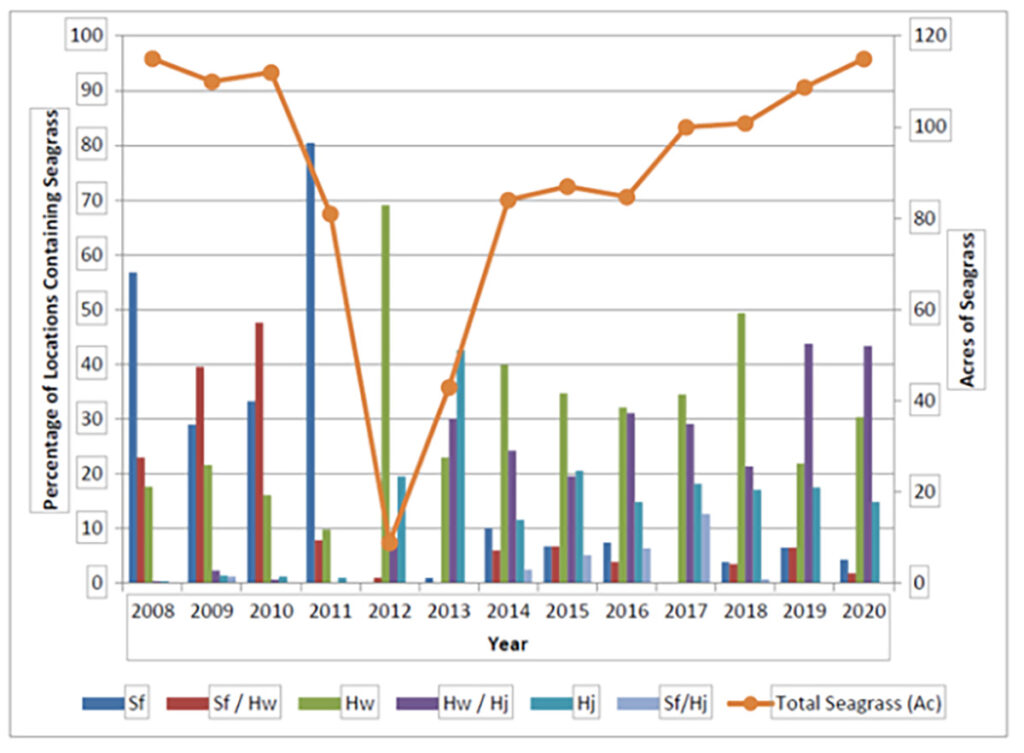

Shoal grass and Johnson’s seagrass continue to be the dominant species with observed manatee grass returning to the flood tidal shoal in the last few years.

In the past (2008-2011), manatee grass and shoal grass were the dominant types, and Johnson’s seagrass was a minor component; however, after 2012, shoal grass and Johnson’s seagrass have been dominant.

“The return of manatee grass could be a sign of recovery,” said Don Deis, marine biologist from Atkins North America and project lead for 13 years. Johnson’s seagrass is a listed threatened species and has played a huge part in the recovery of the shoal. It occurs mixed with shoal grass, manatee grass or by itself in around 64% of the investigated sites.

Interestingly, the Johnson’s seagrass is a unique population segment in the Indian River Lagoon system.

The water exchange, or flushing, between the Indian River Lagoon and the Atlantic Ocean has a positive impact on water quality within the lagoon, and has promoted an accelerated resurgence of seagrass beds on the western flood shoal at the Inlet as compared to other parts of the lagoon.

Those seagrass beds are home to a highly diverse group of plants and animals, including microscopic bacteria to copepods, shrimp, blue crab and juvenile fish, and 70% of Florida’s marine recreational fish depend on seagrass communities at some point in their life cycle.

Data collected is shared with partners including the St. John’s River Water Management District to coalesce lagoon-wide data for analysis and year to-year comparisons.

During the August 2020 groundtruthing effort, biologists visited the 16 potential prop scar locations identified in a July aerial image, assessing them for validity. No prop scars were field verified from the aerial imagery.

This is a change from 2019, when 34 prop scars were field-validated; however, prior to 2019 the number of prop scars validated during survey events was typically low.

The District has created presentations, videos, and media posts to educate the public on the importance of protecting and preserving seagrasses in the ecosystem to reduce these propellor impacts.

“Prop scars can be devastating to seagrass beds and take an average of 10 years to heal naturally,” said Sebastian Inlet District Executive Director James Gray.

“The District placed markers around the six zones reading Caution, Shallow Water, Seagrass Area and marked the navigational channel in 2008 as an aid to boaters. The District also distributes a free inlet Navigation Guide so boaters can enjoy the area in an environmentally responsible way,” Gray added.

Seagrasses are flowering, saltwater plants that live in the shallow areas of an estuarine system. They not only act as a nursery and food source for juvenile fish, shellfish and manatees but also improve water quality by trapping and removing sediment and nutrients suspended in the water column.

Seagrass roots and rhizomes stabilize sediment in the lagoon bed, and established beds help protect shorelines and limit erosion. The drift algae collected within the seagrass is an important component in the collection of nutrients within the lagoon.

According to the St. John’s River Water Management District, 2.5 acres of seagrasses can support up to 100,000 fish, up to 100 million invertebrates, and $5,000-$10,000 in economic activity.

The full technical report is on the Sebastian Inlet District website.

Figure 1: Six zones of seagrass area on the western flood tidal shoal at Sebastian Inlet

Figure 2: Predominant seagrass species/species combinations observed from 2008 to 2020.

- Sf = Syringodium filiforme (Manatee Grass)

- Sf/Hw = Syringodium filiforme/Halodule wrightii (Manatee Grass/Shoal Grass)

- Hw = Halodule wrightii (Shoal Grass)

- Hw/Hj = Halodule wrightii/Halophila johnsonii (Shoal Grass/Johnson’s Seagrass)

- Hj = Halophila johnsonii (Johnson’s Seagrass)

- Sf/Hj = Syringodium filiforme/Halophila johnsonii (Manatee Grass/Johnson’s Seagrass)

About the Sebastian Inlet District

The Sebastian Inlet District was created in 1919 as an independent special taxing district by act of the Florida State Legislature and chartered to maintain the navigational channel between the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian River. The Sebastian Inlet District’s responsibilities include state mandated sand bypassing, erosion control, environmental protection, and public safety.

The Sebastian Inlet supports a rich and diverse ecological environment that is unparalleled in North America. The Inlet is vital not only to the ecological health of the Indian River Lagoon, but it is also an important economic engine for local communities in the region.

Known as the premier surfing, fishing, boating, and recreational area on the east coast of Florida, the Inlet is one of only five navigable channels that connect the Indian River Lagoon to the Atlantic Ocean.